How the US money system works

Understanding the nuts and bolts of how the US monetary system works might seem daunting. And I'm not going to lie, it kind of is. But by the end of this piece you'll understand the basic details of its setup and operation.

Every country's monetary system is set up slightly differently, but the fundamentals translate pretty well. They might differ in division of responsibility between government agencies, differences in banking regulation, and differences in operating procedures. I chose the US system because it's the one I'm most familiar with and also because it's the world's dominant monetary system, with relevance far outside America's domestic borders.

Let's start with the players

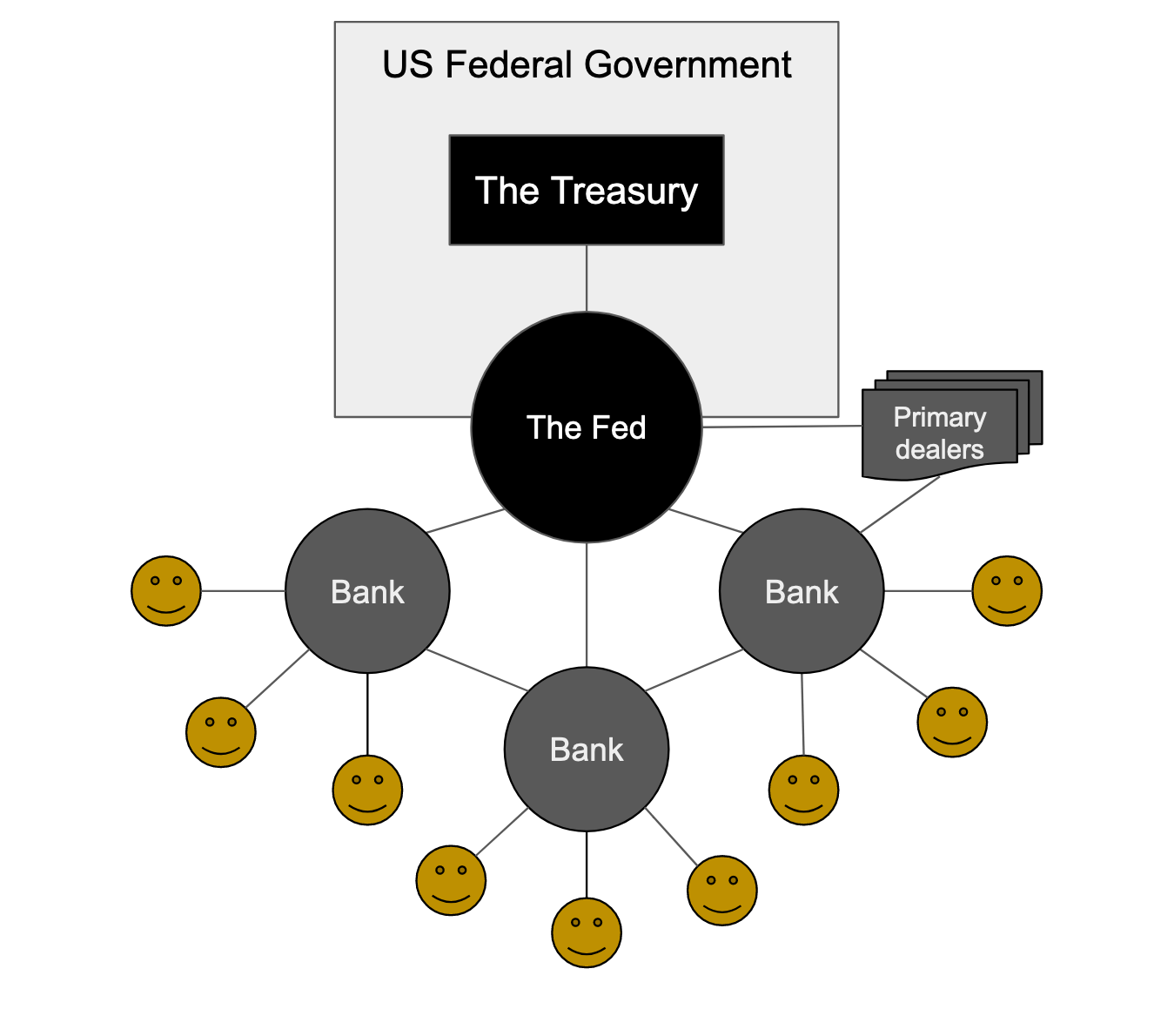

Before diving in, let me just introduce you to the key players. At the top there is the US government, which includes the Congress, the Executive branch led by the President, and the Judiciary. The Congress makes the rules, including the rules of the monetary system, by passing laws, usually requiring the President's signature as well. The same lawmaking process also authorizes spending. According to rules laid out in the Constitution, the executive branch cannot legally spend a dime except through careful adherence to the instructions given to it in the laws passed by Congress.

Within the Executive branch, there are two key organizations that are charged with administering the monetary system: the US Treasury and the Federal Reserve.

Technically, only the Federal Reserve Board is a Federal agency, with the rest of the Federal Reserve System being a closely interconnected set of public institutions that sit under the direction of the Federal Reserve Board. I will simply refer to the Federal Reserve System (the Fed, for short) as a US federal government agency—to do otherwise in this context is splitting hairs. The Federal Reserve was first established by the 1913 Federal Reserve Act, and has operated since then as the US's central bank. In its role as the central bank, it issues a key digital form of the dollar, called a "reserve", that can only be held by chartered banks, foreign central banks, and a small number of other financial and government institutions.

The US Treasury is a department of the US federal government. It is one of the oldest and is mentioned in the US Constitution (alongside the postal service), and its formal structure as a department was established by one of the first acts of Congress in 1789. Today, the US Treasury is a massive organization, employing over 100,000 people. Of its many bureaus, four in particular are directly responsible for issuing or managing the issuance of the major official forms of money held by the public. The US Mint, America's oldest monetary institution which can be said to predate the US itself, is responsible for minting coins, including the penny, the nickel, the dime, the quarter, and the less-used dollar coin, as well as numerous collectible coins. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing is responsible for printing the paper money. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) is responsible for regulating the chartered banks that issue bank deposits, the most widely used form of the dollar, a responsibility it shares with the Federal Reserve and other government instrumentalities including Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Finally, there is the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, which oversees the issuance of Treasury securities, including Treasury bills, a form of the dollar that is most widely used to store large cash balances in the millions or billions, due to their superior interest and safety features. Treasury securities are often called simply "Treasurys" (yes, with this odd spelling), so that's the term I'll use here.

Each of these forms of money has their own quirks—while they are substantially similar to one another, they are also each different in important ways. Together, these five types of money—bank deposits, coins, paper currency, Treasurys, and reserves—make up the broadest range of what you might call "official money" of the US.

Also within the Treasury is a key bureau—perhaps the key bureau—that quietly underlies all money. That is the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which is responsible for administering federal tax collection. The only ironclad promise that the US government makes about the five forms of money described above is that it will either accept them as payment, or guarantee their convertibility into something that it accepts as payment, for the purposes of any legally enforceable obligation, including government fees, court judgments, and, importantly, taxes.

Finally, one cannot discuss our monetary system without including banks. While no single bank is a big player the way the Treasury or the Fed is, the banks taken together play a key role. In fact in our day to day, we rarely (if ever) interact with the Fed or the Treasury directly. This is because while these governmental institutions stand at the core of the monetary system, Congress has set up our monetary system so that almost all interaction with it is intermediated by private banks, keeping the government at arm's length from the daily business of making loans, managing retail storefronts and ATMs, and carrying out our payment instructions. It is key to recognize that banks are not simply like any other private company, and have both special privileges and special obligations in their role as agents of the government within the monetary system.

How the system fits together

Here's a stylized diagram of the US monetary system:

The Fed and the Treasury

The Treasury and Fed each play complementary roles, with their separation being perceived as politically and culturally very important. In this setup, the Treasury represents the US government, while the Fed is supposed to operate at arms length from (the rest of) the government. In practice, however, they are by necessity deeply interdependent with one another, as actions each takes affects the other on a day-to-day basis such that neither can achieve its goals without coordination, and both are accountable to the Congress that created them.

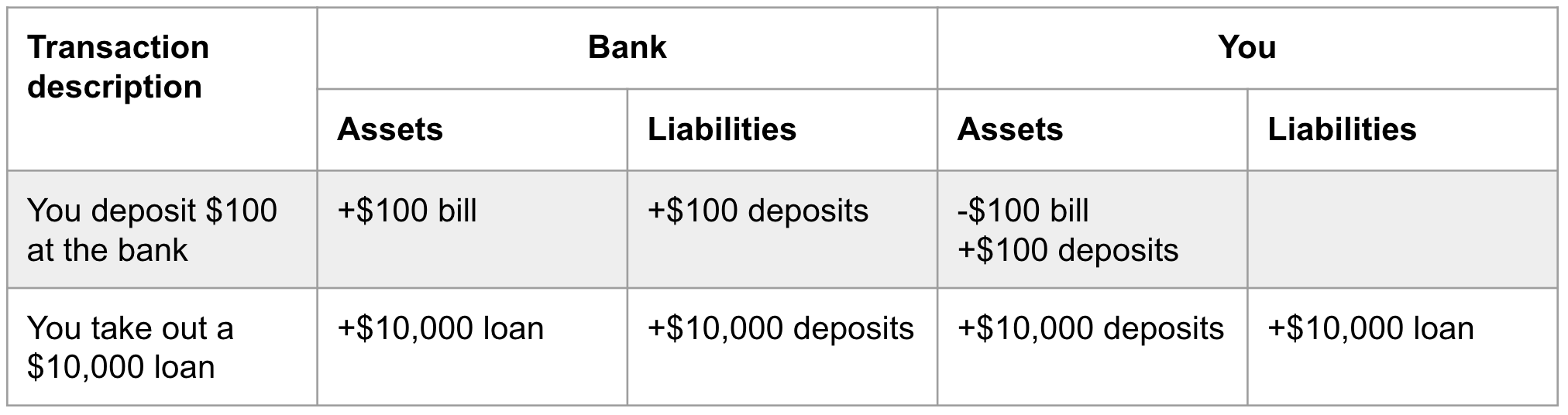

The Fed is set up like a bank. A bank (any bank) holds assets and issues liabilities, primarily bank balances. If you deposit a $100 bill at a bank, your bank balance goes up by $100; the $100 bill is now the bank's asset, and the $100 of bank balances is your asset and the bank's liability. Banks can also issue bank balances without anyone giving them any kind of money first. When a bank makes you a loan, the bank takes your loan agreement as its asset, and issues bank balances to you as the matching liability. These two transactions are shown below in terms of their effects on the assets and liabilities of the bank and of you. This type of summary, displaying assets on the left and liabilities on the right is called a "T-account" and it is a common way of showing transactions. In this one, each row is its own transaction, and shows how that one transaction affects the assets and liabilities of each party.

The Fed is set up like a bank, holding financial assets and issuing a similar amount of liabilities, but it has some extra superpowers. By design, it issues the best money in the entire monetary system, called "reserves" or settlement balances. It's the money that's at the top of the hierarchy of money within the dollar system, and it's the only money that can be used to pay taxes to the Treasury—something your bank does on your behalf.[1] Alongside this superpower it has another: unlike private banks, who are required to maintain a sufficiently positive net worth (sufficiently more assets than liabilities), the Fed has no such requirement. In fact, currently its net worth is around -$155 billion. When you're the government, and you run the monetary system, this poses no particular issue. When the Fed does have a positive net worth, it transfers any excess above a certain amount to the US Treasury.

The Treasury has an account at the Fed. Remember that since these are both government bodies, this is essentially intergovernmental accounting, similar to a husband and wife keeping track of how much they owe one another. Still, they follow strict rules for this accounting, since it poses few practical problems and reinforces the important political perception of separation between the two. One of the accounting rules is that the Treasury must keep a zero-or-greater balance at the Fed at all times. The Treasury can do this in a few ways—technically when the government issues coins, this increases the Treasury's balance at the Fed, for example—but the main way it does it is by issuing Treasurys, which the Fed does on its behalf. We'll say more about this later.

Private banks

Meanwhile, private banks also maintain accounts at the Fed. The balances in these accounts are called "reserves" or settlement balances. The banks use these balances to settle payments with one another, and with the government. But normal people and firms are not allowed to have accounts directly at the Fed. Instead, we have accounts at these private banks. The balances in these accounts are called "deposits". Reserves are issued by the Fed, so they are unambiguously government-issued money. Deposits on the other hand are issued by private banks, and guaranteed by the government up to $250,000 per account-holder per bank, through the FDIC. Deposits are also highly regulated. Thus bank deposits are still an "official" form of money, and in some sense they are still "government money", because they are still a contingent liability of the government.

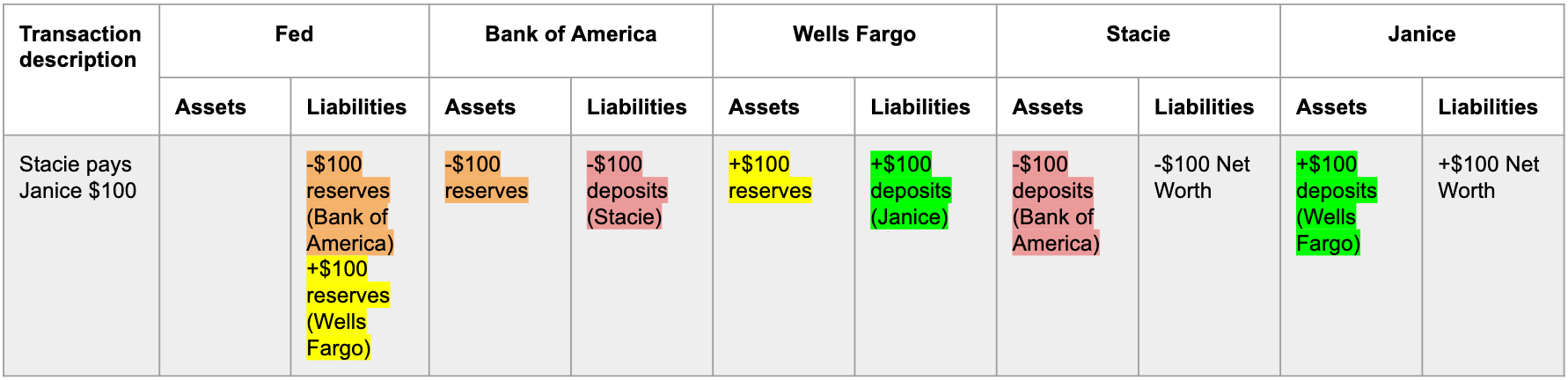

To see the relationship between reserves and deposits, let's look at an example. When one person makes a payment to another person through the banking system, the banks adjust each person's bank accounts and then settle up with each other using their own accounts at the Fed.[2] If Stacie who banks at Bank of America sends Janice who banks at Wells Fargo $100, the transaction would look like this:

- Stacie's account at Bank of America ("deposits"): -$100

- Bank of America's account at the Fed ("reserves"): -$100

- Wells Fargo's account at the Fed ("reserves"): +$100

- Janice's account at Wells Fargo ("deposits"): +$100

The t-accounts for this are shown below. Each change to a bank balance shows up twice, once as a liability of the issuer and once as an asset of the account-holder, and I've color-coded it to make it easier to spot these pairs. By convention net worth is displayed on the liability side, which by identity makes the two sides always balance. It's also nice because then you can spot who got richer or poorer in a transaction.

Note here that Wells Fargo receives one type of money ("reserves") and gives Janice a different type of money ("deposits"). Reserves are nothing more than a number in a database at the Fed, and deposits are nothing more than a number in a database at each bank—albeit numbers that carry legal weight. If you ever imagined any physical currency moving as part of this transaction, note that nothing remotely like that takes place.

Physical currency

So how does physical money get into people's hands? A key feature of the monetary system is that every dollar of deposits, reserves, paper money, and coin money has the same value—they exchange for each other 1-to-1. For this to be the case, the government makes sure that there is a highly functional system for converting any one of these into any other. The most widely used form of money is bank deposits. People can ask to "withdraw" them as cash—paper bills or rolls of coins. The bank keeps around enough currency in their ATMs and with the tellers to meet the demand for withdrawals. Banks in turn, can buy cash from the Fed via a debit to their reserve balances: their reserve balances goes down, and they get cash. Finally, the Fed gets the cash from the Treasury in whatever quantities it requests, and it makes sure to keep around enough to meet the expected demand from banks.

This means that the amount of paper currency in circulation isn't something that the government actively decides. Rather, the government, in order to maintain perfect 1-to-1 exchange between each form of money, passively accommodates the public's demand for each denomination of currency versus bank deposits. If people start asking their banks for a much higher volume of $2 bills (the ones with Thomas Jefferson on them), then the government will issue more of those to meet that demand. As it happens, $2 bills are somewhat uncommon; this is not because the government refuses to print them, but simply because people don't ask their banks for them much.

Treasury securities

You may have been surprised by the inclusion of Treasurys in the above enumeration of the forms of "the dollar". And it's true, Treasurys are usually referred to not as "money" but as "debt". It's important to realize that there is no natural, objective place to draw the line between "money" and "debt". A debt is a promise to pay. But what is a bank deposit—money—if not a bank's promise to make a payment on your behalf? Even physical currency is an a sense the state's debt. Money is best thought of a specific category of debt that is highly acceptable.

Many banks offer customers a higher rate if they transfer their normal deposits into a term deposit account, usually called a CD ("certificate of deposit"). The government offers something similar: Treasury securities. Most people would call CDs "money", albeit money that's locked up for a time. Most large holders of dollar cash prefer to hold Treasurys over bank deposits or CDs, because they're both safer (no exposure to bank failure above that $250,000 limit) and typically offer a modestly higher rate of interest. Banks themselves typically like to hold them instead of reserves for the higher interest as well.

I like to call Treasurys "money" or "a form of the dollar" because "debt" typically carries with it a connotation of a real possibility of default. But in the case of Treasurys, a default could only be the result of an serious unforced error on the part of the government; it would conceptually be as absurd as the government refusing to convert its own paper currency into reserves. Whether you want to call them "money" or not is honestly a matter of taste and context. Regardless, Treasurys are crucial to many of the basic operations within the US monetary system.

The way that Treasurys get into the system is more complicated than paper currency and coins. First, a detour is required to understand exactly what happens when Treasurys are purchased from the government.

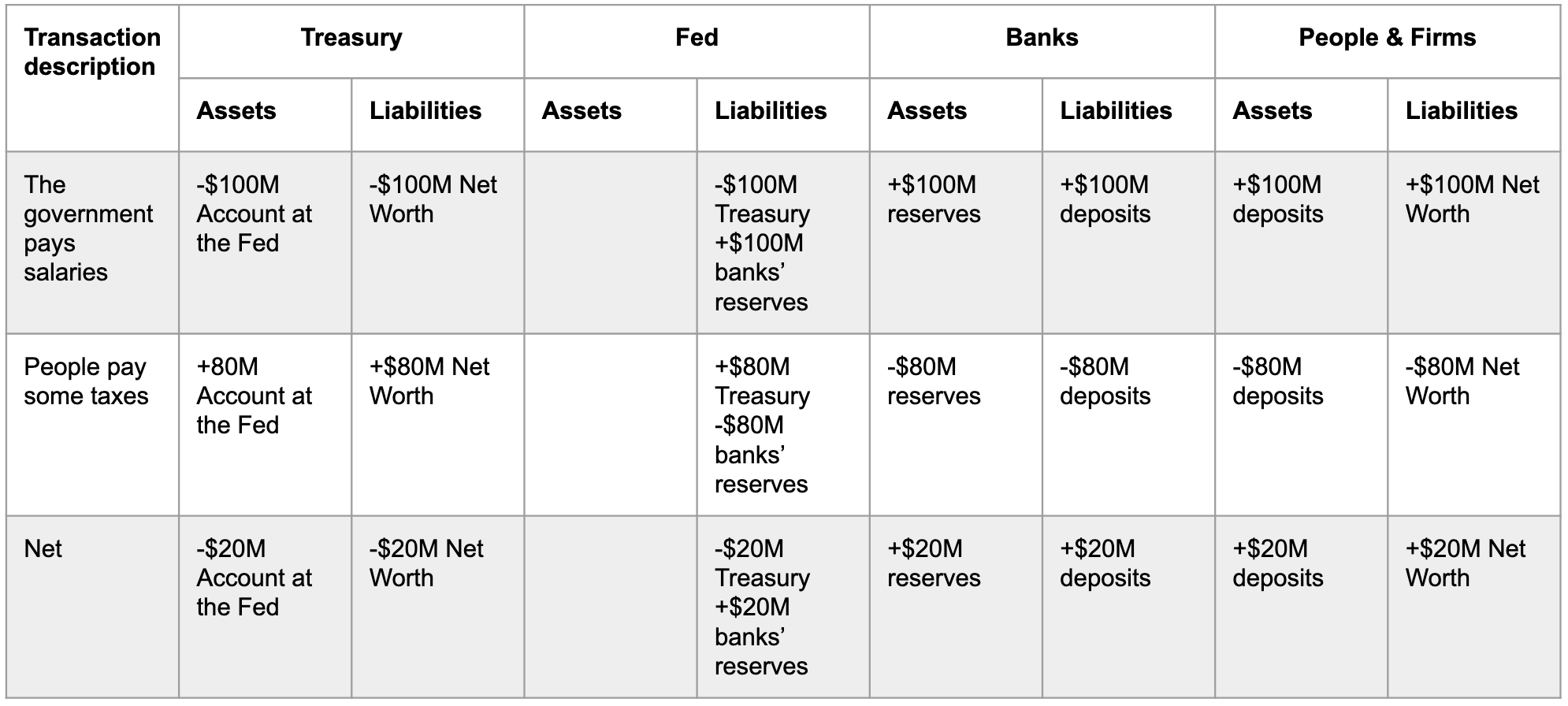

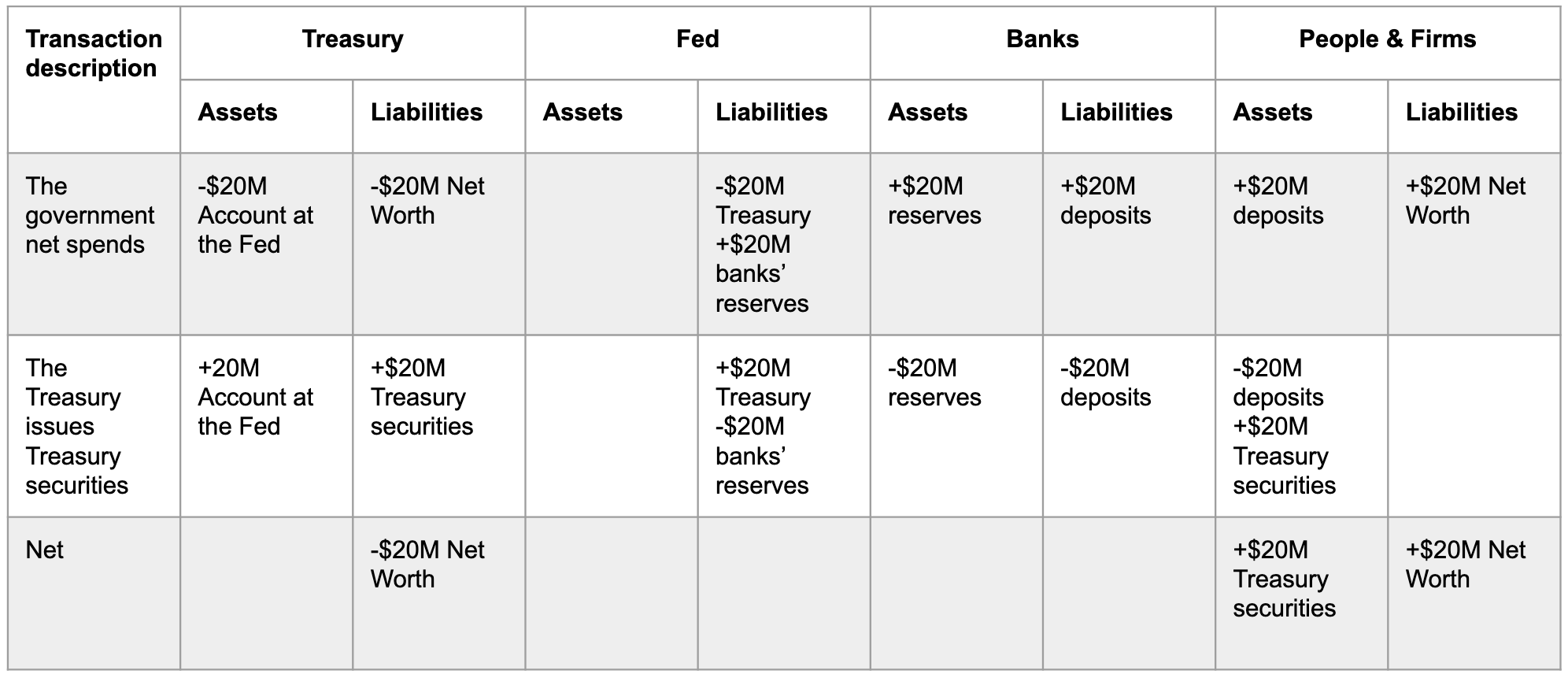

When the government spends, the Treasury's account at the Fed goes down, and banks' accounts at the Fed (in the aggregate) go up. This is because if the payments are going to individuals, the Fed will credit the reserve account of their bank, and then their bank will credit their account. This is shown in the first transaction below.

When the government receives taxes, the same operations happen in reverse: banks' reserve balances go down and the Treasury's account at the Fed goes up. This is shown in line two. Typically, the US government is a net spender over any given period of months, and so the net effect of government outlays and receipts is that the Treasury's account goes down and banks' reserve balances go up. This is shown in the final row, which nets the first two rows.

The government aims to have its day-to-day operations keep reserve balances at a relatively stable level by default, and the laws governing the operations of the Fed and the Treasury are written in a way that support this. In order to keep reserve balances at a stable level, the Fed and Treasury must offset the tendency for banks' reserves to continually increase over time as the government net spends. The way they achieve this is by requiring the Treasury to maintain a non-negative balance at the Fed and to continually refill its account by issuing Treasurys. Banks pay for these Treasurys with reserves (and debit the end buyer's deposits as well if the bank isn't the end buyer) and this results in the reserve balances declining.

This set of transaction picks up where the last one left off. After the government net spends, the Treasury issues Treasury securities, exactly undoing the effects that the net spending had on both the Treasury's account at the Fed and on banks' reserve balances. You can see this in the final row which nets the previous two. This still has the net effect of reducing the Treasury's net worth, but just as we saw with the Fed, there's no particular problem with the Treasury having a negative net worth from a legal or account perspective. Roughly speaking, it stands as an accounting record of the money it has spent into the system that it hasn't yet taxed back out. You can see that represented as the +$20M of Treasury securities and the +$20M of Net Worth sitting with People & Firms in the above example.

So how exactly does the Treasury get these Treasury securities into the system? To make sure that the Treasury is always able to issue the amount of Treasurys it wants to on the exact days it wants to in order to offset the reserve effects of its spending, the Fed and Treasury have devised a reliable setup. The Treasury tells the Fed how many types of each security it wants to auction on what days, and announces this to the public. The Fed conducts the auction with a small number of financial institutions specially designated as "primary dealers", of which there are only a couple dozen. In order to remain a primary dealer, each of these institutions is required to participate in every auction. Furthermore, they are required to place bids for their proportional share of the total, and these bids are required to be "reasonable", by the government's judgment. The effect of this is that these Treasury auctions are always oversubscribed, and the Treasury is reliably able to issue the amount it requires to meet the above goal.

You may have seen people in the financial press wonder out loud where all the money to buy all the Treasurys is going to come from. This question really doesn't make very much sense. If you look at the transactions above, you can see that the money to buy the Treasurys—specifically, the reserve balances that banks use to settle the payment—comes from the government's own prior act of net spending. Government spends, reserve balances go up; government auctions Treasurys, reserve balances go back down to their original level. If the primary dealers specifically are tight on bank deposits on a particular day, the Fed stands ready to lend them whatever amount they need to cover the day's Treasury auction, and it does this regularly. Once the primary dealers have resold the Treasurys, they repay the loan, typically on the same day. The primary dealers almost never have any trouble finding buyers—banks would almost always prefer to hold Treasurys rather than reserves—but on the rare occasions of market turbulence, the Fed is also more than willing to buy the Treasurys off the primary dealers, and has done so on numerous occasions. Again though, this is almost always unnecessary: in the normal course of operations, the money to pay for the Treasurys comes from the government's prior act of net spending.

Conclusion

There was a lot to cover in this piece, from the institutional details to the underlying accounting—behind each detail here, there are a thousand more. And I left some whole areas out, including the role of the dollar in the global financial system. Still, I hope that this piece presented the high-level overview necessary to understand how the different parts of the domestic US monetary system operate together. When I began this piece, I knew it would be somewhat of a slog. But when I thought of the other pieces I wanted to write, so many of them relied on a basic understanding of the monetary system. In order to not have to get sucked into even longer digressions in every piece I write, I knew I had to get this out of the way. I hope the slog is worth it for the future discussion it allows. Regardless, congratulations: if you made it all the way through, you now know more about the US monetary system than the vast majority of people. And, I might add, based on what I've seen, more than many people who should really know better.

[1] You are technically allowed to use physical cash to pay taxes, but good luck.

[2] If Bank of America doesn't have enough reserve balances at the Fed, this does not pose an immediate problem: their account simply goes negative. This is called a daylight overdraft, and Bank of America is expected to cover it by the end of the day. This doesn't pose a problem to Bank of America either, because banks regularly borrow reserves from each other in what's called the "fed funds market" or "inter-bank market", and the rate at which they lend to each other is something that the Fed rather effortlessly maintains in a narrow band as a matter of policy, through fairly simple techniques which are nevertheless beyond the scope of this piece. The Fed also stands ready to lend reserves to banks itself. In other words, running out of reserves is essentially a non-issue for banks. In fact, the Fed no longer requires banks to hold any reserve balances at all, an indication of how easy it is for banks to get them when they need them. Failure to maintain a sufficiently positive net worth, on the other hand, will get a bank shut down quick.