What's the relationship between public spending and taxpayers?

Author's note: Thank you for all of your support so far. I'm still just getting started, and I'm trying out different topics and styles. I've enabled feedback buttons for members, so you can use those to register your appreciation or displeasure, and as always feel free to reach out to me directly to share feedback. You can also find me on Twitter at @dannydrob (which I use less of nowadays) and on Bluesky @dannyroberts.bsky.social.

This piece is about an idiom and the mental model behind it. Take a look at these New York Times headlines from the last year.

Some headlines from the New York Times, 2023-2024

They're about a variety of topics, and they all mention taxpayers. But if you read closer, none of them are really about taxes or the process of paying taxes at all. Instead, they're about government expenditures. This probably doesn't strike us as particularly unusual. After all, using taxpayers to represent the use of public funds is a common idiom.

I'm interested in this particular idiom, though, because it conveys a mental model that can be taken at face value. Most idioms are never meant to be taken literally. If you refer to the randomized control trial as "the gold standard" in public health research, no one is confused that you might mean that it is literally a monetary system involving gold. But it is often unclear whether the taxpayer idiom is simply a common turn of phrase, or it is intended to be interpreted as a serious claim about how government financing works.

For example, when Margaret Thatcher famously said, “There is no such thing as public money, only taxpayer money”, it's hard to interpret that in any other way than an exhortation that this idiom is not just an idiom, but is in fact a serious theory of government finance. It's less clear, taking one of the headlines as an example, whether when New York Times says "Taxpayers Were Overcharged for Patient Meds" they're intentionally trying to push a particular way of understanding government finance or just using a common idiom.

I personally try to avoid this kind of slipperiness in language and to use analytically neutral language when talking about complex subjects, so in my own writing and speech, I use phrases like "the public" or "public money" in these instances. Of course, people will continue to use the phrases that they're used to using.

In this piece, I will use this idiom as a gateway to explore the mental model that underlies it. First, I'll briefly lay out the model. Then I will explore the idiom itself and the subtler messages it conveys. Finally, I'll take some time to explore how the model stacks up to the reality of government finance.

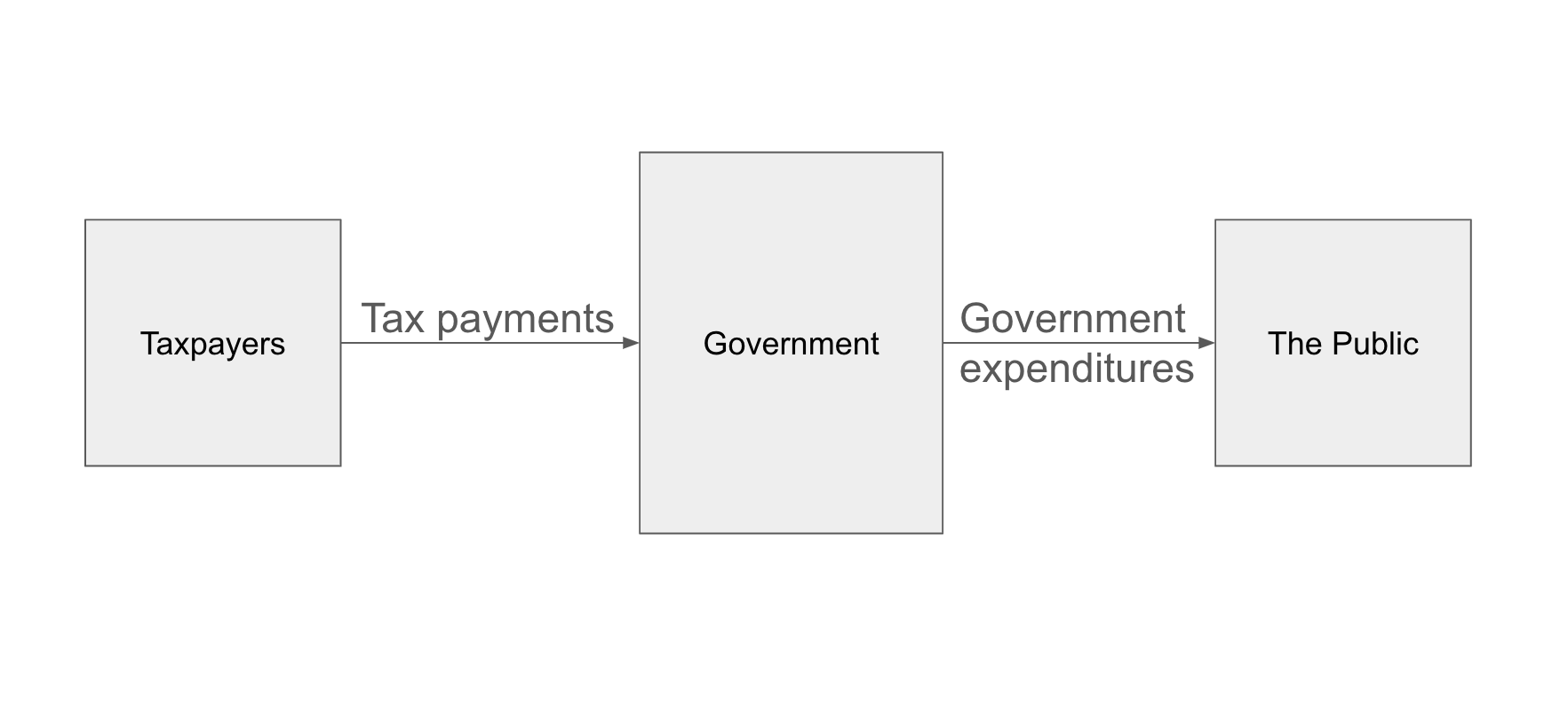

The Taxpayer Money Model

The basic model underlying the taxpayer idiom is fairly obvious. The model is that the government pools money from taxpayers, and then spends that money. In this model, the government might spend a little more or a little less each month or each year than it collects, by either maintaining a buffer in its account (that it got by collecting taxes earlier) or by borrowing (which it'll need to collect taxes to repay), but over longer periods they basically balance out, so you can basically ignore these small time-period mismatches. At the end of the day, in this model, all of the money the government spends is coming from taxpayers, past, present, and future, dollar for dollar, penny for penny. More spending by governments means less money for taxpayers. That's the idea.

The Taxpayer Idiom

For now let's simply accept this model as a given. First, I want to explore the wording of the taxpayer idiom itself.

There is something a little funny about the phrasing. When we refer to public expenditures as "taxpayer money" we're identifying the funds being spent with the second-to-last party to hold them. It would be like saying that a sales rep who spent their paycheck on a new sofa was spending "company money". The reason this sounds funny is that we tend to only identify funding with the second-to-last party when the last party is seen as a passthrough entity that only exists to represent its fund-suppliers. For example you might refer to a small non-profit's funds as "donor money" if the non-profit is seen as really just a facilitating agent for the donors, who are the principal actors. Or you might refer to how a fintech company uses "customer funds" to emphasize their fiduciary responsibility to the customers. Or perhaps a company may refer to its own expenditures as spending "investors' money", to emphasize their responsibility to investors.

But philosophically, in a democratic society, do government funds still in some sense "belong" to taxpayers after taxes have been collected? This is, of course, up to the reader. Legally speaking, they definitely do not: after taxes are collected, taxpayers have no special legal claim on government that is tied to the size of their tax bill, in sharp contrast to depositors in a fund or investors in a company. According to my own values, governments certainly have a responsibility to allocate and spend funds wisely, but that responsibility is to the public in general, not to taxpayers specifically. The government is equally accountable to all members of the public regardless of the size of their tax bill. I would argue that this is a basic premise of democracy.

How does the model stack up to reality?

It's one thing for me to highlight philosophical issues with the framing embedded in the idiom. But that aside, how accurate is the model itself?

Spending at the local level

In a very broad sense, the model gets one thing right: taxes are crucial to the provisioning of governments. But from there it gets muddier.

Currency-issuing governments like the US federal government are perhaps a special case. So let's start instead with a currency-using government like the state of Texas. For such governments, taxes feed into the funds they then have available to spend, so they're a good reference case to see how the taxpayer money model might work in the real world.

One difference that becomes apparent right away is that they may have significant sources of revenue besides taxes. The state of Texas, for example, gets less than half of its revenue from taxes. It gets about a third of its revenue from the federal government, which the federal government issues directly. A full 20% of it comes from fees, fines and other revenue. So even in a state government, where the norm is balanced budgets and limited borrowing, the taxpayer money model misses something important.

Another way that the model falls a bit short of a more complex reality is that it understates who "pays" when there are higher taxes. High taxes really can be a burden—but when they are, they are typically a burden on a much broader swath of society than just taxpayers.

Let me give you an example. In Texas, we have a sales tax and a property tax, but no income tax. Since only businesses pay sales tax and only property owners pay property tax, many people in Texas don't pay any taxes directly at all. But tax rates still directly affect them. A higher sales tax means everything's more expensive, and a higher property tax means rent is more expensive. The money to pay the tax is coming just as much from shoppers and renters as it is from taxpayers. More broadly, when taxes are too high compared to the volume and composition of government spending, people tend to cut back on their spending. This can result in higher unemployment. In this situation the unemployed are the victims of taxes set too high, at least as much as the taxpayers. The taxpayer money model's implication that taxpayers are always the primary victim of higher taxes is thus too reductive.

Spending at the Federal level

Unlike at the local level, at the US federal level tax policy and spending policy are extremely loosely coupled. In nearly every one of the last hundred years, the US has engaged in significant net spending, with expenditures far greater than receipts. The process it uses when it does this is outlined in more detail in my last piece, How the US money system works, but the upshot is that it issues multiple forms of money, and the net spending accumulates in the hands of the public, mostly as Treasurys and deposits in the banking system.

This is something substantive that the taxpayer money model is missing. In the taxpayer money model, the government's spending outflows must be matched by its tax inflows, perhaps not in a year but over some sufficiently long period. But it's quite clear from the historical data that the federal government faces no such constraint. It sets tax policy and spending policy mostly separately, and on average the amount it spends is a lot more than the amount it taxes—over its history so far, about $27 trillion more.

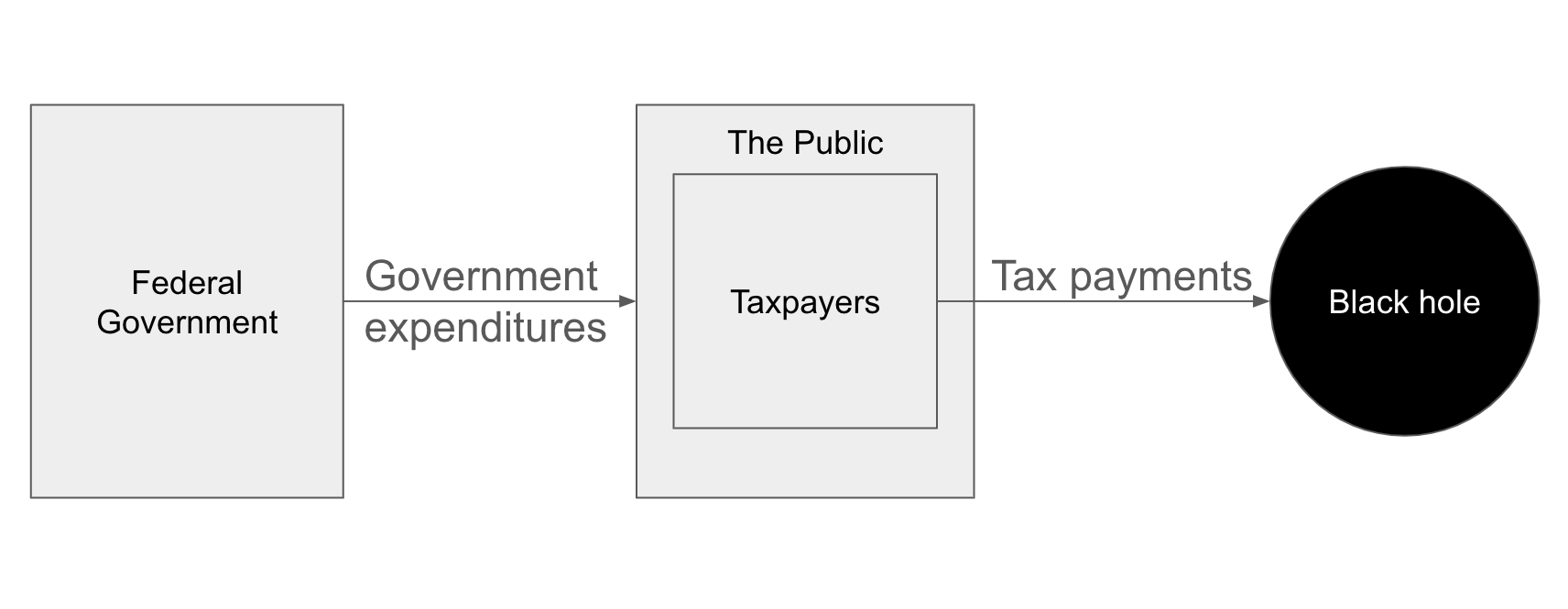

The taxpayer money model has the power of simplicity, and nothing beats simplicity. So here is a model that is just as simple, but which better captures the dynamics of government finance for a currency-issuing government like the US federal government:

In this model, tax payments aren't accumulated; they simply go into a black hole. This represents the fact that money itself is a liability of this government, and how much it issues is its prerogative. Governments in this position don't "have" or "not have" money; they're in charge of the system of accounting that defines what money is. Again, I am describing this casually, but you can see my earlier piece for the details of what I mean by this.

There can be serious consequences to the volume of government spending by a currency-issuing government, and there are limits to its ability to effectuate desired outcomes through spending. Still, while the broad tax structure and its demand effects are quite relevant to the effectiveness of government spending policy overall, the volume of taxes collected is simply not a relevant constraint.

Based on this, I'm comfortable saying that the taxpayer money model maps particularly poorly onto the federal government. Still, it may help to dwell a bit on the effects of spending to build a better intuition for the constraints the government does face, since without that this "black hole" model can be quite disorienting.

A detour on the effects of government spending

Suppose the government sets a particular tax code and just leaves it there, and then develops a stable pattern of spending that it adjusts more frequently. This is approximately what the federal government does.

Now what happens if this government increases its spending by $1000? First, by definition, someone's income goes up by $1000. Second, that person can expect to have their income tax bill increase by maybe $200 because of this higher income. Third, they may decide to spend some of it, which means someone else gets a bit more income and pays a bit more in income tax. Notice that "taxpayers" now have a higher tax bill, just like you might have predicted from the taxpayer money model! But of course, it's the recipients of the income themselves that are paying the taxes because they have more income. This is hardly the burden on taxpayers implied by the taxpayer money model.

When spending increases—whether from the public sector or private sector—it will either put idle resources to work or it will bid up prices (inflation!). In jargon, it will either raise real GDP or raise the price level. Some speak as if inflation is the only possibility, but in practice, historically, incremental increases in spending most often simply lead to more things getting produced and sold. Companies typically maintain inventories in case spending picks up and start increasing production when they notice their inventories falling. Since at all times there are millions of people in the US looking for jobs who haven't yet been able to find them (unemployment), if speeding up production requires hiring more people, that's often not a problem. This is, of course, a stylized view of how this works when it's working well.

When it doesn't work well—when there's really not much production left to be squeezed out of the economy, or when spending is directed at a particular sector of the economy that's already struggling to keep up—then the same spending instead bids up prices. This is one potential source of inflation, but since it is the easiest kind of inflation to avoid and correct, it historically hasn't been the most relevant source of persistent periods of inflation. Still, we should factor inflation risk into fiscal policy as it's being written, probably a lot more than we currently do.

While increases in GDP are typically thought of as a good thing, it is highly correlated with resource use and emission of waste, which degrade our natural environment. And obviously no one likes inflation. These consequences of poorly designed spending policy can be quite severe. But I don't think there's any case to be made that either can be said to be a burden on taxpayers specifically. So even when trying to understand the consequences of spending-gone-too-far, the taxpayer money model doesn't offer much insight.

To really try to fit the taxpayer money model, you could say that in response to inflation, or in anticipation of it, the government will increase taxes, and those taxes burden the taxpayer. To me this is a serious stretch. Tax increases are almost never actually the main government response to inflation in practice, and there's no automatic reason to expect them to be. Our Congress does have a sort of rule-of-thumb aspiration to raise taxes that will match all additional spending (they like to boast that things are "paid for" because they think that appeals to voters), but in practice this mostly doesn't happen, and certainly not on average over time. Try as you might to stretch the taxpayer money model to fit the realities of US government finance, it remains an awkward fit.

Conclusion

For better or for worse, the taxpayer idiom and the taxpayer money model are a fixture of public discourse. They're used effortlessly by people across the political spectrum, politicians from Bernie Sanders to Ronald Regan, journalists at every news outlet, and everyday people from every background. Perhaps you view them as old friends you'll stick by despite any minor flaws the haters might find. Or perhaps you see them a zombies that just won't die. Either way, the taxpayer idiom and the taxpayer money model are here to stay.

My only hope is that today, you gained a new way to think about them.